Jump To:

The travels

The data

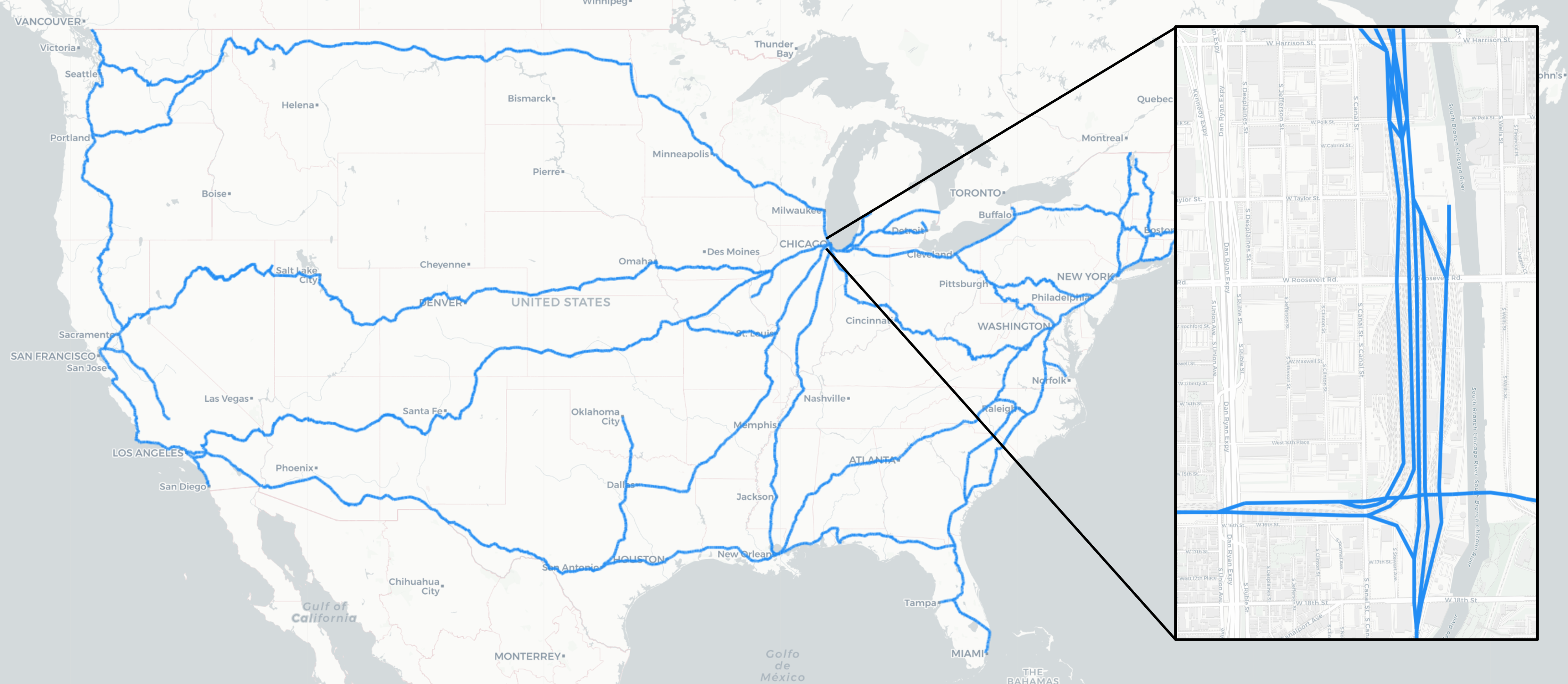

(click the map for an interactive version)

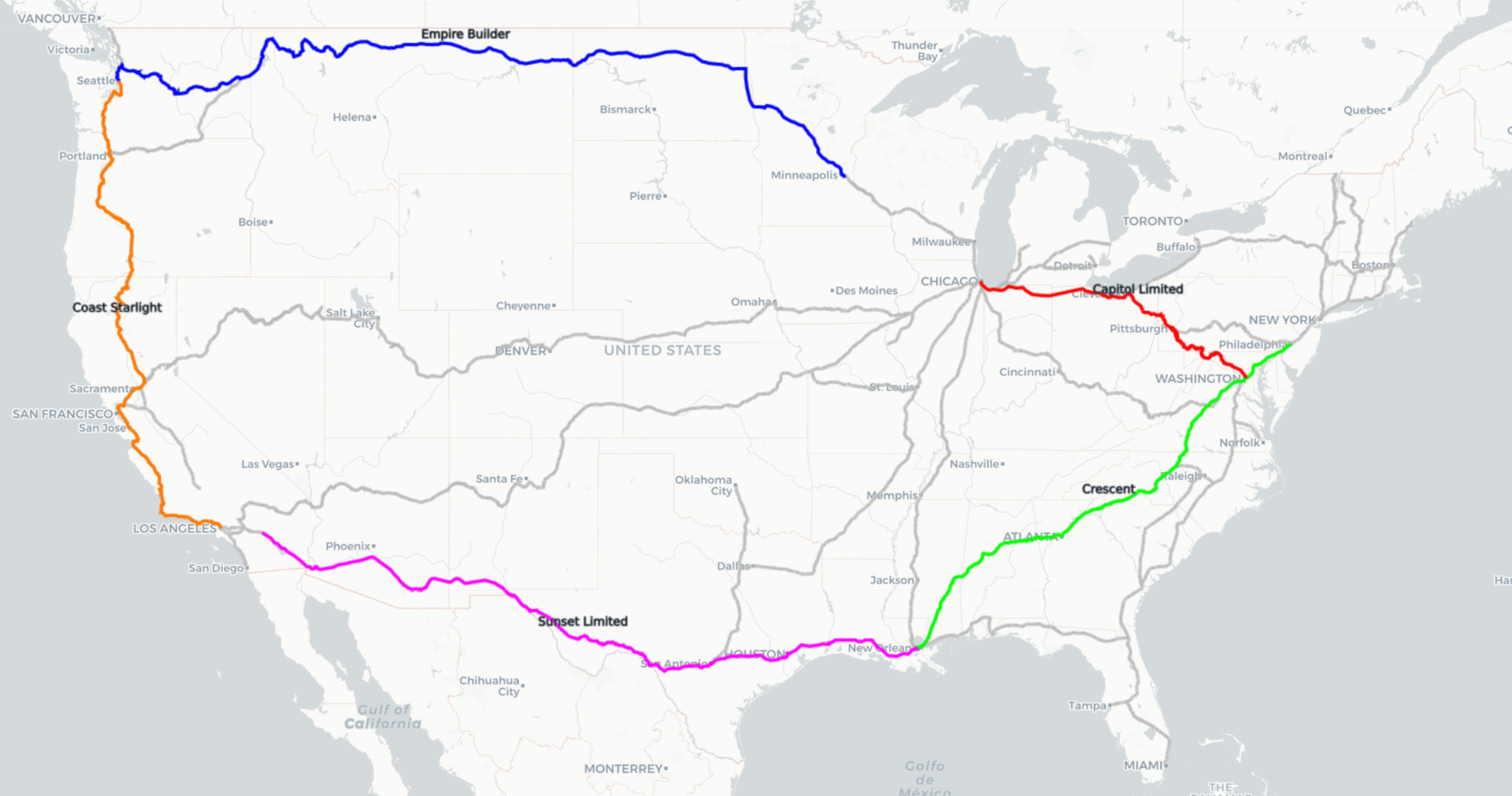

(click the map for an interactive version)

In March of last year I found myself in an unusual situation. I was nearing the end of my graduate research project, but was still missing the bulk of the experimental data I needed. I had already designed the experiment, modeled and built the diagnostic, and tested what I could, but I was waiting on the scintillator for my neutron detector to be built by the manufacturer. With mounting impetus to move towards graduation I found I had little to do in the lab, but plenty to do towards writing my thesis. So I grabbed my laptop, a mountain of research papers, bought myself an Amtrak rail pass, and took off for a three week trip around the United States.

I wanted to create this post because after coming home I had wanted to put some pictures from my trip on a map showing the route I had traveled. Messing around with the Amtrak geojson data turned out to be a lot messier than I had expected, and resulted in some fun bits of programming that I thought would be fun to put up on the site.

The adventure itself

My train adventure began, interestingly, with a bus ride to St. Paul, MN where I made my first stop for my nephew’s birthday party. My parents dropped me off afterward at the Amtrak depot and I climbed aboard. What struck me first is the vast difference in security from airline travel. With two backpacks (one for clothes, one for my camera), I presented my ticket and just… walked on. The larger clothes bag I stored in a luggage rack on the lower level before ascending to the (spacious) seating on the upper deck. Here the seats reclined nearly flat, with enough leg room to extend my feet without touching the back of the row in front of me. Such roominess turned out to make all the difference in comfort as I’d be spending many nights aboard the train over the next few weeks.

Departing from St. Paul late in the evening I quickly fell asleep and awoke in the plains. After my first full day of work, spent mostly at a table in the observation car, night descended just as the train began to climb into the foothills of the Rocky Mountain range. By next morning we were winding our way down towards the coast with a beautiful early sunlit view of the Cascades as we came in to Seattle. A short bus ride to Tacoma brought me to the hotel where Steph was staying for the week working with her Epic client. I stayed the week there with her working from the hotel lobby and reveling in the majestic view of Mt. Ranier. After her work week we drove back up to Seattle and spent the weekend with my cousin Anne, enjoying their company along with the sights and sounds of this wonderful city.

From here Steph took off for Madison and I boarded my next train, the Coast Starlight, headed south towards LA. It was a beautiful and productive leg, and I disembarked at the LA terminal where I stayed a night at the cheapest hotel I could find before taking the train West a few stations to where I was picked up by my friend Dan Carmody in the morning. We drove out to Idyllwild, CA where I spent the weekend with him at AstroCamp playing in the woods, even hiking up to the Tahquitz fire watch tower.

He dropped me off in the morning for my next leg aboard the Sunset Limited which took me along beautiful lonely stretches of desert along the Mexican border as we passed through the southern states en route to New Orleans. In New Orleans, like in LA, I had planned on just sleeping at the station, but once there opted instead for a cheap hotel which always turned out to be the right decision. I took the evening to walk around this lively city to enjoy its vibrant atmosphere. The following morning I was back on the train, this time aboard the Crescent which would deliver me to Washington DC.

I walked from the DC station to my cousin Bob’s place where they put me up. DC was in bloom, so the time we spent walking around this historic city was scented and colored with a springtime liveliness. After dinner and drinks and a bird stuck in the dryer vent I took a short commuter rail up to Philadelphia. I had some time to kill before meeting cousin Dan, so I swung by a popular burger place, awkwardly stashing my two backpacks as close by as possible to limit my annoyance to the other customers. After work we took another short rail commute out to his house where I stayed a couple nights. After a delightful visit and an impromptu game of Go on a makeshift board they dropped me back off at the station where I connected back down to DC. I only had a few hour layover there before my train left for home, but was happy to be able to spend that time with Marty, Hilary, and Winnie, and Dan and Anna.

The Capitol Limited was my last leg. I disembarked in Chicago where I jumped on a Megabus to take me back to Madison. My train travels took me to 24 states over 3 weeks. I saw mile after mile of beautiful countryside as I chipped away at my thesis. It was an incredible experience, and an unforgettable trip. Thank you to everyone who put me up- cousins Jim, Anne, Bob, and Dan, and my good friend Dan Carmody. I relied on you to make this trip a possibility and it was truly a highlight of an amazing trip to get to spend time with each one of you.

Data and Mapping

I wanted to create a visualization for this post using Carto primarily because I haven’t used it before and wanted to familiarize myself with it.

The first step was acquiring data to plot the Amtrak routes, as I wanted these as the basis over which I applied my trip narrative. A simple google search leads to numerous links from which one can easily download a geojson file containing the Amtrak routes. Upon inspection, I found that this file contains every Amtrak route broken up into segments typically less than a mile in length, but notably lacks an easy way to segment the tracks by which trains operate on them. The Empire Builder, for example, runs from Chicago to Seattle across the northern states, but the data lacks a property identifying any given segment as belonging to this particular train.

There are numerous other properties, and I tried a great many ways to use these to my advantage, but continually ran into issues resulting from what I consider a very messy (and frustrating) database. For example, a property is included that identifies a subdivision which usually contains a large number of track segments, but not only are these subdivisions not unique (the subdivision “Lafayette” is not only a part of the Sunset Limited route, but can also be found in southwest Indiana), not all track segments are part of a subdivision. The same is true for the property “FRAARCID” which, given the fact that it ends in “ID”, I may be forgiven for assuming would represent a unique segment identifier. There is even a “To” and “From” property for each segment identifying which track segments connect, but here it was found while trying to piece the routes together that these identifiers are not unique and therefore create problems when trying to correctly link segments end to end to create the individual train routes. The saving grace for this dataset, and the fact I exploited to my advantage, was that each segment shared the same point (to within what I assume were rounding errors in the data entry) with its connecting segment(s).

To create the routes, I basically linked segments together from origin to destination using a fun bit of recursive programming. To begin, I created a unique identifier for each segment by merely creating an index array of features from the geojson FeatureCollection. I also created a start-point and end-point array for each segment; this was essential so that once I knew which segment came next as I built the routes, I would know in which order to add the coordinates listed in that segment depending on if it were the “start” or “end” of that segment that adjoined the end of my route.

By identifying the start and end points for a route (say St. Paul, MN and Seattle, WA for my trip on the Empire Builder), I set the code off on linking segments together to build the route. The need for recursive programming arises because there are obviously more than one way to get to Seattle from St. Paul. The code starts building segments together until it reaches a bifurcation, then calls itself for each direction possible. Whenever the end of a track is reached (or if the desired end-point is reached), the route is saved. In this way we can create every possible route from St. Paul to Seattle and simply choose the Empire Builder from them.

I would argue to say I’ve had the code running for the past few days, but two major difficulties arose using this method that needed to be addressed in order to produce results using this method. One is a memory limitation, the other is a redundancy in the results, but both arise from the same underlying issue. Consider the map below, depicting all the Amtrak routes across America with an inset of a particularly messy interchange in Chicago.

This map highlights the fact that this data does not represent Amtrak routes, it actually is a dataset of Amtrak tracks. So not only does my program look for all routes from St. Paul to Seattle, including those that go through Chicago, it looks for all possible track combinations as well. The enormous number of permutations of tracks leads to the two issues mentioned above in that it both pulls my CPU into the abyss, and produces a huge number of routes that are essentially identical (though passing along different tracks as they traverse Amtrak stations).

My solution to the memory issue was to track the level of recursion. It seems that my CPU can only handle 45 or so nesting calls to a function at once, so to prevent the memory issue whenever the nesting level reached 40, the route is saved in a temp file and the routine returns up a level. In effect, this finds all routes from the starting point that require 40 levels of recursion. Once done with that, it then starts opening these partial routes (with the entire partial route now at level 0) and continues building. While a limit at level 40 suffices, in practice I set the level limit to 20 to save some CPU for whatever else I want to be doing.

While technically functioning at this point with the memory solution in place, a huge number of routes are generated due to the track redundancy- so many that starting from St. Paul my computer struggles to build routes much further than St. Cloud. If left long enough I am confident it would work as designed, but ineffectual programming isn’t very fun. To alleviate this problem I needed to essentially remove information, or more accurately tell the program what information to ignore. To do this, I apply a smaller version of the recursive programming already developed. Using the index ID already in use, I scan each junction to see if the track bifurcates (noted by three or more segments meeting at one point). At each bifurcating junction I then trace out all possible routes of a certain length (5 connected segments suffices). I then identify redundant track segments by finding paths whose last segment is found within another path before the last segment. In effect, I’m identifying which paths extend the furthest from the starting point, and then keeping track of all the extra track segments that are within range but not used by these far-reaching paths.

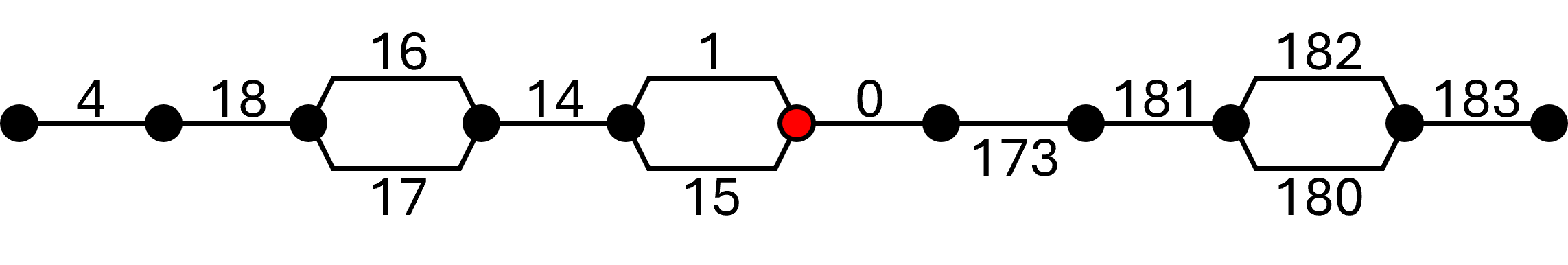

Some visuals might help explain my method here. Consider this cartoon of a real junction in Mississippi.

Starting from the red node, the routine identifies these possible paths of length 5:

paths = [[0, 173, 181, 180, 182],

[0, 173, 181, 180, 183],

[0, 173, 181, 182, 180],

[0, 173, 181, 182, 183],

[1, 14, 16, 18, 4],

[1, 14, 17, 18, 4],

[15, 14, 16, 18, 4],

[15, 14, 17, 18, 4]]

I identify the furthest reaching paths by identifying which paths have final segments that do not occur in the first four segments of the rest of the set of paths. So in the case above, the 2nd and 5th paths are identified as the furthest reaching (others with the same end segments are ignored). The redundant segments are those that occur in the set of paths listed above, and do not occur in our list of furthest reaching paths. Applied here, this results in redundant segments of 15, 17, and 182.

By compiling a list of these redundancies and feeding them into the recursive route-building routine we can ignore a great deal of the complexity in the dataset and more effectively build the routes we’re looking for. Additionally I can manually add segments in order to prevent unnecessary route searching (I can, for example, prevent the recursion from looking East out of St. Paul). I can now quickly obtain all the routes of my journey, with no gaps, overlaps, or other ugly features.

The routes of my tour

The routes of my tour

It is amusing, however, to see what the computer can come up with. I took the time to write a recursive algorithm, may as well have some fun with it. I am working on a way to present all the possible routes from St. Paul to Seattle, but there are many possible routes, and displaying them clearly is difficult. Perhaps in the future I’ll create a gif or something. For now, here is one of the longest ways to get from St. Paul to Seattle (without doubling back over any already-traveled track segment).